Two Minnesota Flax Stories

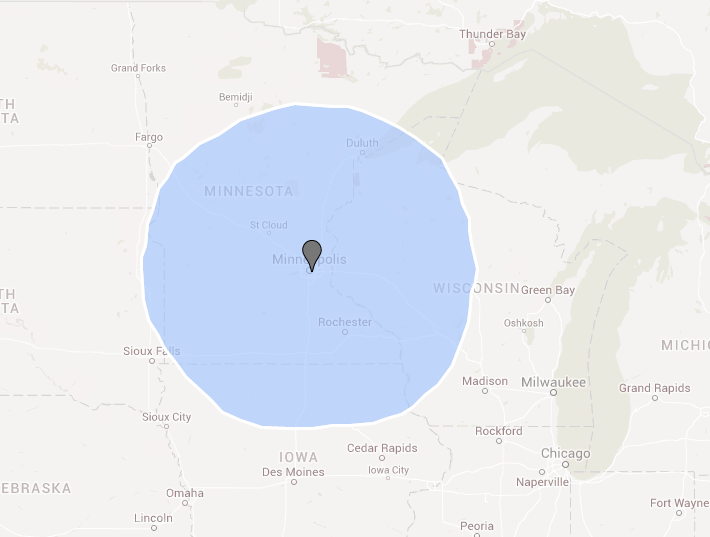

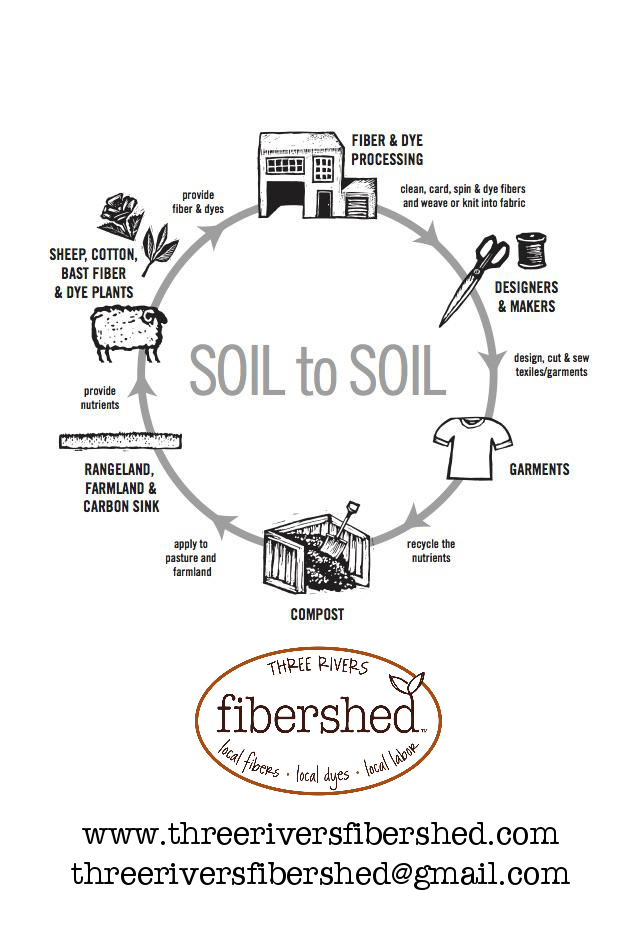

Flax is an ancient fiber, cultivated for over 10,000 years and used for the production of textiles. Linen, the cloth made from flax, is incredibly durable and renewable making it an environmentally friendly choice for clothing and other household items. Flax is also a popular fiber among hand spinners, knitters, weavers, and papermakers. Flax grows well in our region, being well suited to flourish in our medium-heavy soils and cool temperatures. However, it is time consuming to harvest and process. To further complicate matters, no regional infrastructure currently exists to process flax into linen and other finished products. But this has not stopped two local women from delving into the revival of locally grown flax.

In the spring of 2017, Andrea Myklebust, the proprietress of Black Cat Farmstead, was awarded a grant by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Sustainable Agriculture, Research and Education program to grow textile flax in western Wisconsin and to have a portion of the crop processed on newly-developed machines at Taproot Fibre Lab in Port Williams, Nova Scotia. The development of Taproot’s processing machines has eliminated the historic barrier of lacking the appropriate flax-processing machinery. Andrea’s project is exploring the feasibility of developing a local linen industry. Her vision includes: growing flax in an organic rotation on a diversified farm, then utilizing mechanical processing equipment to turn that flax into linen products such as line flax, tow fiber and roving, and handmade paper. If you’d like to read more about Andrea’s project including an in-depth progress report, check out the SARE project page here.

In 2017, the Duluth Hand Crafters Fiber Guild (DHFG) announced an experimental project for members to grow flax. Terry Andre Dukerschein, a member of DHFG, was gifted some flax seeds from another fellow member who had grown flax in that first year. During Memorial Day weekend of this year, Terry scattered her flax seeds onto a 9 x 10 foot plot in her garden. The day was hot and dry, but by the end of the week rain had fallen and shortly after flax seedlings had emerged! With more rain, the flax grew fast and Terry found that it was at least knee-high by the fourth of July. By the end of the month it was covered in tiny blue flowers. In September the plants were pulled up and thus began the long process of converting the flax plants into fiber. Terry is hoping to be able to spin her flax and turn it into exfoliating pouches for soap and bath products.

The possibilities and approaches to growing and working with flax in our region are endless as these two experiences within our local fibershed highlight. Are you growing flax in the Three Rivers Fibershed region? Would you like to see flax play a larger role in our regional fiber system? Leave your comment below!

Bios:

Andrea Myklebust is a sculptor, shepherd, and textile artist living in rural Stockholm, Wisconsin. In addition to her work with flax, she tends a mixed flock of about eighty sheep, and turns their wool into a variety of products for sale. She is passionate about working with local fiber and strengthening local and regional textile infrastructure. Follow her on Instagram at Black Cat Farmstead, or www.blackcatfarmstead.com and catch her via email at myklebust.sears@gmail.com.

Terry Andre Dukerschein belongs to multiple regional fiber guilds and arts organizations. She knits, crochets, felts, hand-spins with wheels and spindles, and hand-processes some of her farm’s wool. Terry and her husband live on Glen Tamarack Farm in Wisconsin, where they raise fine-fleeced Shetlands and are focused on Conservation Grazing. Find more information about her farm at https://www.glentamarack.com and reach her at glentamarack@gmail.com.